Solving Raging Rapids

Alternative title: How to spend a few hours over the holidays sitting at a computer.

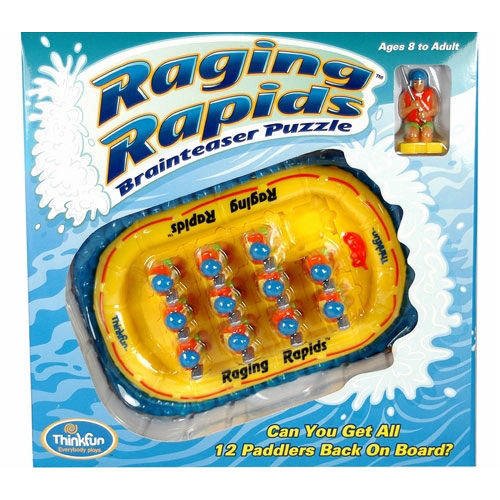

A few years ago a friend of mine sent me a puzzle called Raging Rapids.

The basic puzzle is can you put all 12 paddlers into the white water raft? At the base of each paddler are jigsaw style piece ends along each side. The edges of the raft also feature similar puzzle features. The goal is to put all 12 rafters in the raft facing the same direction. There are actually two solutions, as the rafters can fit in both facing the back of the boat and the front of the boat.

The puzzle arrived on Christmas Day and by the late afternoon I was looking for a diversion to keep me from eating more cookies. After spending a few minutes playing around with the pieces and trying to do it by hand, I realized that I wasn’t smart enough, so I start writing some code for it.

Brute forcing it won’t work. At least not on the computer I had at the time – though I’m certain that there is some clever distributed mechanism that I could have used to spread it over a few different boxes. Or spun up a server. Let’s just say that the chromebook that I had at the time (dev mode unix) wasn’t going to suffice. There are \(12! \approx 479\text{MM}\) possible solutions to test.

Searching this space is tricky: you need to know not only the shape of the edges on the raft, but also the shape of edges on the a joining pieces in order to be certain that two pieces match. Annoyingly? Importantly? The pieces themselves are unique.

Given this, I spent some time looking for some “easy wins” that would collapse the solution space. The “A-Ha!” moment came when I recognized that the corners of the raft, which had two sides defined by the raft could only fit a few pieces. Implementing this meant that the possible solution space went from \(12!\) to roughly \(8! \approx 40\text{k}\), something even the little chromebook that could would be able to finish.

I labeled the pieces (A-L) and spots (0-11), wrote up a couple of helper functions which would evaluate if pieces could fit together and viola! Solution found. Sadly, the person who sent me it was disappointed. – he thought I cheated.

A couple of take-aways:

- This was really fun!

- The hardest part was setting up the data objects which defined the shapes. There were a number of different types of sides and I wanted to find a way that would allow me to use matrix math operations (rather than for loops) to determine if pieces fit. The initial way that I set this up didn’t facilitate these operations and I ended up having to back and recode each piece.

- I was certain that the code was correct and kept getting no solution. You know why? ‘Cause when I entered in a few of the pieces I mis-typed what them. Once I fixed my data entry, the code ran without a hitch … until it found another error.

- The code I wrote wasn’t particularly clean or well-documented. I was surprised, however, at how easy it was for a non-coder (my sister) who was there at the time to walk through the logic with me. It is really a testament to the value of domain knowledge as a means of learning. We (including myself) often tend to think of skills as black or white – can a person do X? Often the reality is a bit more gray: my sister caught some logic errors I had by applying first principles with a bit of matrix knowledge and not a lick of coding skills.

Finally, if you want to jump to the solution, feel free to look at my git repo. There are some more comments in the code and without the toy I’d expect it to be difficult to figure out what I did.